When Breaking a Ceiling Becomes Just Another Footnote

Justice Nagarathna’s 36-day appointment isn’t a milestone. It’s a mirror and it won't erase decades of discrimination.

Since 1950, India has had 51 Chief Justices of the Supreme Court. Every single one has been a man. Now, after more than 75 years, Justice B.V. Nagarathna is projected to become India’s first woman Chief Justice in 2027 for a grand total of 36 days.

A historic moment, no doubt. But let’s not kid ourselves: this isn’t a triumph. It’s a glaring indictment of how deeply gender inequality is baked into the Indian judiciary. And anyone who says “change takes time” has either not been paying attention or is too comfortable with the way things are.

The absence of a woman Chief Justice isn’t an accident. It’s the result of decades of underrepresentation, systemic barriers and social biases that started from the very beginning. Women entered the legal profession in smaller numbers, much later than men.

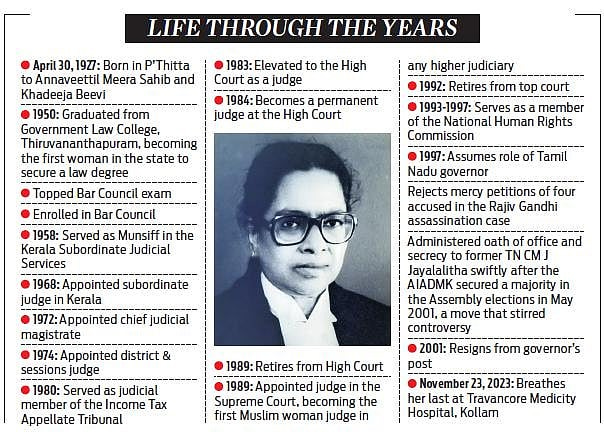

Justice Fathima Beevi became India’s first woman Supreme Court judge only in 1989 — nearly 40 years after independence. With so few women ever appointed to the Supreme Court, the pool of candidates eligible for the Chief Justice’s office was practically nonexistent.

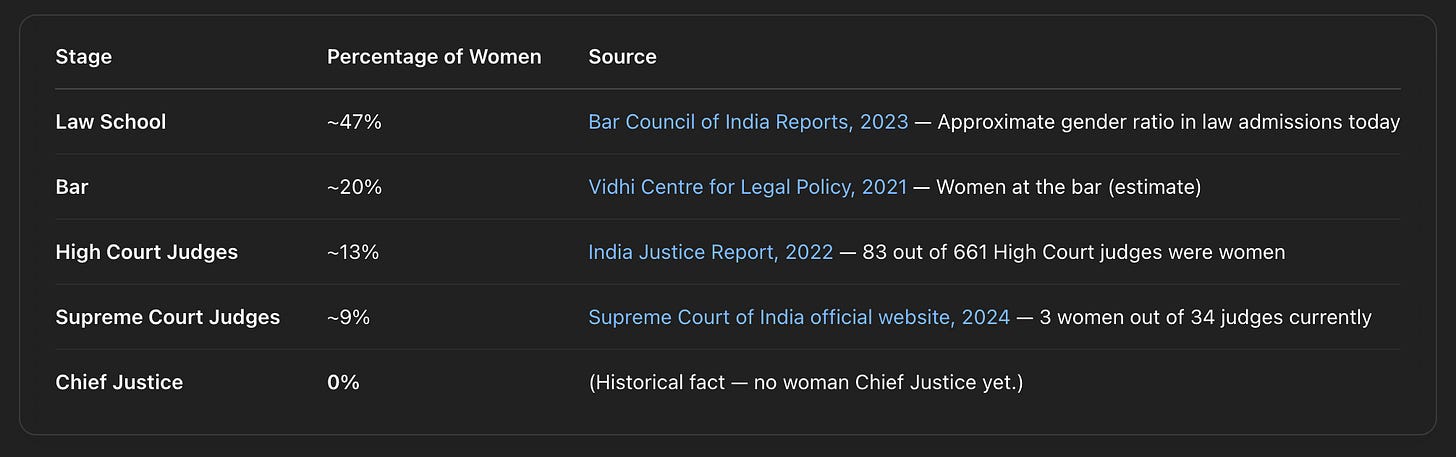

The higher judiciary is typically drawn from senior advocates and High Court judges, spaces that have historically been male-dominated. It’s a pipeline problem: if women aren’t given opportunities at the start, they simply can’t make it to the top.

Late Justice Leila Seth’s story captures this pipeline problem perfectly. When she first approached a senior lawyer to join his chambers, he told her to “get married,” “have a child,” and even “have a second child” instead of giving her the opportunity to practice. She persisted and eventually became India’s first woman Chief Justice of a High Court. Her experience wasn’t unique, but it reflects a system that actively pushed women out at every stage.

The Supreme Court follows a seniority convention: the most senior judge is appointed Chief Justice. On paper, it sounds objective. In practice, it perpetuates inequality.

Since women were kept out of the judiciary for so long, they often enter later, serve shorter tenures and don’t accumulate the seniority required. Hence, seniority, in a system built on exclusion, is not neutral. It’s just a polite way of saying, “wait your turn” in a game rigged against you from the start.

Critics argue that seniority is essential to maintain impartiality and that merit, not gender, should decide appointments. But this assumes the playing field was ever level to begin with. If systemic biases have kept women from building seniority in the first place, then defending seniority becomes a defense of inequality, not fairness.

Justice B.V. Nagarathna herself, speaking at a conference in 2022, pointedly said, “We must not mistake historical imbalance for natural outcomes. Systems, when left unchecked, favor those who have always been privileged by them.”

In contrast, other countries didn’t wait around for the numbers to fix themselves. The United States appointed Sandra Day O’Connor to its Supreme Court in 1981. New Zealand appointed Dame Sian Elias as Chief Justice in 1999. The United Kingdom appointed Baroness Hale as the head of its Supreme Court in 2017. South Africa’s Judicial Service Commission openly interviews judicial candidates, putting diversity front and center. Canada’s Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee ensures transparency and inclusion. Meanwhile, India — the world’s largest democracy — is still looking forward to a symbolic 36-day appointment in 2027.

Beyond the numbers lies a deeper, more uncomfortable truth: social norms have built invisible walls that legal reforms alone cannot break down. Patriarchal attitudes that are deeply embedded in society have long dictated what roles women are expected to play. These attitudes run so deep that even when laws change, behavior doesn’t. As Late Justice Seth observed, even after the Hindu Succession Act gave daughters equal inheritance rights in 1956, many women chose to relinquish their shares — not because they didn’t know their rights, but because they feared upsetting family relationships.

Laws can open doors, but without a mindset change, most women are still expected to quietly step aside. Even though the Pew Research Center survey found that 55% of Indians believe men and women are equally good political leaders, the judiciary remains far from equal. Deep-seated biases continue to shape how lawyers are treated, how cases are assigned and how leadership is imagined in courtrooms.

Gender stereotypes and unconscious biases further complicate the picture. Women in the legal profession are often seen as less aggressive, less decisive or less suited for the tough demands of litigation and leadership. These stereotypes, even when unspoken, affect career trajectories — from who gets assigned critical cases to who is considered “CJI material.”

As Justice Hima Kohli bluntly put it: “Women judges must work twice as hard to be considered half as good.”

Justice Indu Malhotra echoed the same frustration: “We need more women on the bench not just for diversity, but because they bring different perspectives to justice itself.”

The lack of visible role models only deepens the problem. Advocate Karuna Nundy once said, “The absence of women in top judicial positions reinforces the message that the higher you go, the lonelier it gets.” Without mentors and support networks, the path to the top becomes even steeper. Family responsibilities and societal expectations around work-life balance create additional hurdles. The demands of a judicial career—long hours, frequent transfers, constant pressure—often collide with expectations placed on women at home. It’s not that women are unwilling or less capable; it’s that the system is set up in ways that make it almost impossible to do both without extraordinary sacrifice.

When a woman takes a career break or opts for a less demanding position, she loses seniority — and the system conveniently blames her for not “staying the course.”

Meanwhile, the internal structure of the judiciary doesn’t do much better. The collegium system, responsible for appointing judges, operates behind closed doors with little transparency or accountability. Without any deliberate focus on gender diversity, it tends to reward familiarity, which in practice means elevating people who look, think and act like those already in power.

Male-dominated networks at the bar and bench gatekeep access to important cases, critical recommendations and the kind of exposure necessary to build a reputation strong enough for elevation. Women remain underrepresented in senior litigation roles, which shrinks the pool of potential candidates for judicial appointments even further.

And the roots of this underrepresentation go beyond the courtroom. When women are denied economic independence at home — when daughters are pushed toward dowry instead of inheritance — they are systematically excluded from the networks of power that produce future leaders. Denying women their rightful share in the family estate echoes all the way up to the absence of women leading India’s highest court.

Justice Nagarathna’s upcoming appointment will be historic. But it’s also bittersweet. Her 36-day tenure will be so short that it almost feels like a formality. It allows the system to claim progress without making any meaningful structural changes. A woman at the top for just over a month doesn’t erase the fact that the court remained an all-boys’ club for more than 70 years.

If we are serious about changing this, we need more than token celebrations.

First, reform the collegium system: include diversity metrics as mandatory considerations, publish clear evaluation criteria and create public accountability mechanisms for appointments.

Second, set formal targets: at least 33% of the judiciary at all levels must be composed of women within the next decade. Other sectors like the Indian Administrative Services (IAS) have seen visible upticks in women’s leadership once formal diversity goals were established.

Third, adopt global best practices: Canada's advisory panels and South Africa's public interviews show how transparency and inclusion can go hand-in-hand with merit.

Fourth, build mentorship networks: create structured programs led by senior advocates and judges to mentor women consistently, similar to initiatives already adopted by leading law firms like AZB & Partners.

Fifth, modernize work policies: gender-neutral parental leave, flexible work conditions, and mental health support must become standard, making it easier for both men and women to balance professional and personal lives.

And finally, challenge seniority: when seniority upholds discrimination, it cannot be sacred.

We can celebrate Justice Nagarathna’s appointment. But if we stop there, we’re letting the system off the hook. A judiciary that took more than seventy years to find even one woman fit to lead it is a judiciary that has failed half its people.

As Martin Luther King Jr. said, “The arc of the moral universe bends toward justice — but only if we push it.”

A 36-day appointment doesn’t fix a 70-year failure.

If you believe that India's judiciary should reflect the people it serves, not the biases it inherited, don’t stop at reading this article. Support organizations like Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Mentor young women entering the legal profession. Demand greater transparency in judicial appointments. And more importantly, speak up.

As Late Justice Seth wrote in an appeal from a daughter’s perspective:

Father, why do you discriminate against me when I can be as good as my brother?

Mother: nurture, nourish and educate me, and you will see that I will not be a burden but will control my own destiny. Break the bonds of tradition and let me into the sunlight to dance, to dance, to dance.

Justice isn’t just about legal reforms. It’s about changing the sunlight women are allowed to stand in. Because justice isn’t served until it’s served equally.

If you haven’t seen it yet, watch the talk by the Late Justice Seth here:

Numbers for the pipeline graph:

Nice ...

What's situation in lower judiciary ,

No facts and figures about them?

As they are recruited by exam in lower..ig

Is there reservation of seats ???